It was messy and chaotic, but it reminded me how resilient I really am

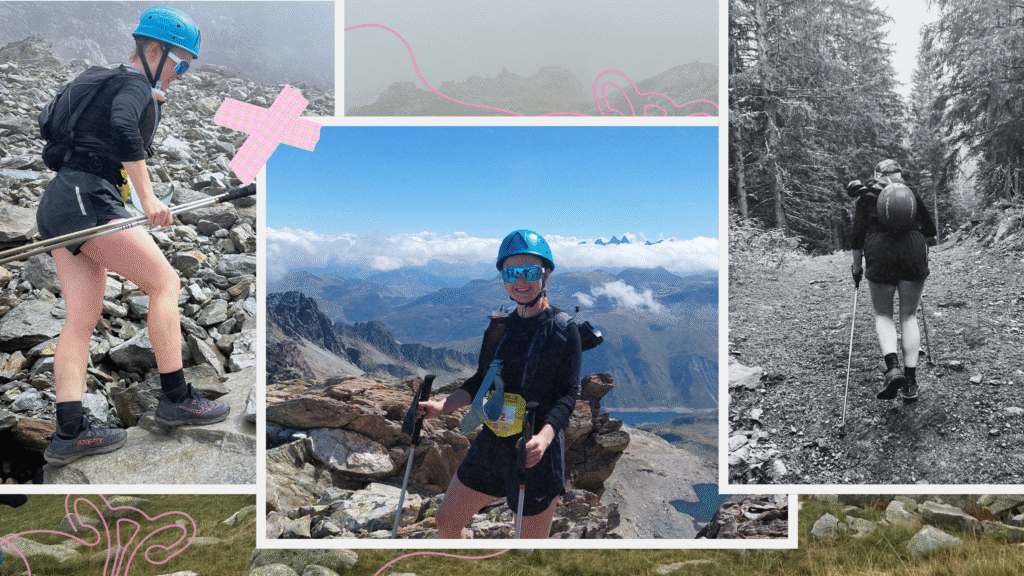

(Photo: L’Échappée Belle: Anna Richards; Design: Cnythzl/Getty, Ayana Underwood/Canva)

Published September 18, 2025 03:00AM

The dense cloud cover cleared enough for me to see the summit, and the speedier runners were already there, looking like tiny lice, trail poles giving the effect of many legs. It was a near-vertical run to reach the peak, tight switchbacks over slippery shale that made my feet slide backwards every time I took a step. After 30 minutes of huffing and puffing, I finally reached the exact spot where their louse-like silhouettes stood, only to realize that it wasn’t the summit. From my new vantage point, the trail plummeted steeply down before climbing again, over a mass of boulders and loose slate to reach Le Rocher Blanc at 9,600 feet.

Bloody, sweat-soaked, and teary-eyed is an apt description for many of the runners partaking in L’Échappée Belle race. Born in 2013, it’s often described as the toughest trail run in France. The loop-shaped route passes through the French Alps’ crystalline Belladonne mountains, uninterrupted by roads and crowned by lakes and scree slopes. Several people cried, particularly at the false summit. Some bled—par for the course when you’re running over boulders, and sweat is to be expected when you’re running 6,562 feet up a mountain to a ticking stopwatch. I, however, wasn’t bleeding due to injury.

I was bleeding because I was on the second day of my period, and at some point, up a mountain and in the middle of an organized race, I was going to need to empty my menstrual cup. I’d inserted my 20 milliliter Nakungoo Cup (which is about the length and diameter of a kiwi fruit), two hours before the race, allowing plenty of time to pick up my race pack. And with the rate I bleed on day two, there was no way my cup was going to hold until the finish line.

I’d never done a proper trail run before I signed up for L’Échappée Belle, and doing this with minimal experience is a little like choosing the Pacific Coast Trail for your first hike. I was tackling the shortest distance, the SkyRace. Its 13-mile length didn’t scare me. It was the 6,561 feet of elevation gain and loss, over terrain so technical that mountaineering helmets were mandatory, that I found terrifying. Each of L’Échappée Belle’s five races has more elevation gain for the distance than even the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc. I’m a keen hiker and I’ve run a couple of (slow) marathons, but trail running? I didn’t even own poles.

My apprehension only increased a few months before race day, when my period tracker broke the news that the race would fall on day two of my cycle. As regular and predictable as the chiming of London’s famous Big Ben, I should not have been surprised. But there’s no natural way I’ve found to stop my period at will. Alas, there I was at the start line, dosed up on painkillers for the cramps, after several bouts of morning diarrhea, clutching a brand new pair of poles, about to run up a mountain. Sure, I didn’t relish the idea of changing my menstrual cup mid-race, but I was more worried I’d shit myself.

The Belledonne mountains’ trails appear as though they have been chewed by a giant mouth and spewed out haphazardly. In other words, rocks were everywhere. It’s a striking beauty, and the SkyRace went past seven high altitude lakes that gave this area its name—Les Sept Laux. When participation in a race is this small, there’s little pomp or ceremony after you cross the start line. I set off with 260 runners. One-fifth of them didn’t make it around in the seven-hour cutoff time, and others were eliminated for failing to make checkpoints within the allotted time. On the longest route, known as L’Integrale, which is 94 miles, the failure rate rises to 50 percent.

The relatively flat section at the start of the trail was short-lived. It quickly began to climb through a pine forest, an obstacle course of roots and boulders. If I didn’t reach the first checkpoint, 3.7 miles in and 3,510 feet up, in under 1 hour and 50 minutes, I’d have been automatically eliminated. Fortunately, I reached the first checkpoint in 1 hour and 40 minutes. But this specific checkpoint lay within a sea of fog so dense I could barely see the first lake. (Naming my seven lakes Snow White-style, I called this one Misty.)

Here was where I was confronted with my biggest challenge: at the beginning of 5.5 miles of high-altitude, the rugged terrain created a minefield of crevasses to ensnare my ankles. I could feel my cup starting to fill up already, but I had a mental block about taking a break to empty it whilst I was still going uphill because—What if stopping made my legs seize up? Wearing a mountaineering helmet was now obligatory. Equipped with a bright blue hardshell and a pair of iridescent sunglasses, I resembled a bleeding, Blue bottle fly zooming up a hill.

I don’t enjoy having my period, but I’m hesitant to call them bad. I don’t suffer from endometriosis or polycystic ovarian syndrome. Still, the cramps can be violent enough to stop me from leaving the house, and the effect on my bowels is a free monthly colonic irrigation. Maybe it was the adrenaline, or perhaps it was the extra dose of pain meds, but running up a mountain seemed to be soothing my womb.

After the false summit, reaching the true peak felt all the more sweeter. I was above the clouds, a sea of them that left the surrounding mountains poking through like islands, with the occasional gaps revealing the navy waters of two other lakes I nicknamed Death Trap and Tiny. On I went, downhill this time, slipping and sliding, feet bashing rocks on all angles, the occasional whistling of marmots serenading me during my descent.

By mile nine, I knew that delaying my cup removal was a risky move. My menstrual cup is close to overflowing at this point. I’ve had to empty it before on hikes, but I’ve had considerably more time, and there’s been far less footfall. I chose a large boulder to hide behind, ensuring I was not too close to running water to avoid contaminating it, and went through the distinctly inelegant process of pulling out my cup in a squat position; using my fingers to pinch the cup slightly was enough pressure to break the suction seal.

I hadn’t thought this through; my trail running water bottle had zero structure, so trying to rinse my cup one-handed from my water bottle meant I showered my arms in water and blood droplets alike. I reinserted the cup, and I carried on. It’s gross not to be able to wash your hands (or your arms) when you’ve just covered yourself in menstrual blood, but at that point, I was just thinking about finishing the race.

The last part of the trail was child’s play compared to what had come before. Forest trails and a relatively gentle decline, so naturally, it was here that I tripped over a tree root and found myself face-first in the dirt. If I’d been worried about arriving less than salubrious after eating dirt and tending to my sanitary needs on the trail, I needn’t have. Because it turns out that L’Échappée Belle’s route came furnished with a natural power washer. Shortly before the finish line, the trail stopped dead in front of a fast-moving river, with a rope strung across to help us keep our balance. At just five feet and two inches, the water was almost up to my waist.

Six hours and three minutes after setting off, I reached the finish line. I was welcomed with a cold beer and the ringing of a giant cowbell, soaked from the waist down, and elated.

As I reflect on that day, I’ll be honest: I wouldn’t do anything differently. I think I handled my period in the best possible way for a one-day race. My trail vest was nearly bursting with snacks, water, sunscreen, and period pain meds. All of that felt more important than, say, packing wilderness wipes when I was going to be able to have a good shower that same afternoon.

It might sound smug, but I felt an extra level of satisfaction in completing France’s most challenging trail at the worst time of the month.

Want more Outside health stories? Sign up for the Bodywork newsletter. Ready to push yourself? Enter MapMyRun’s You vs. the Year 2025 running challenge.