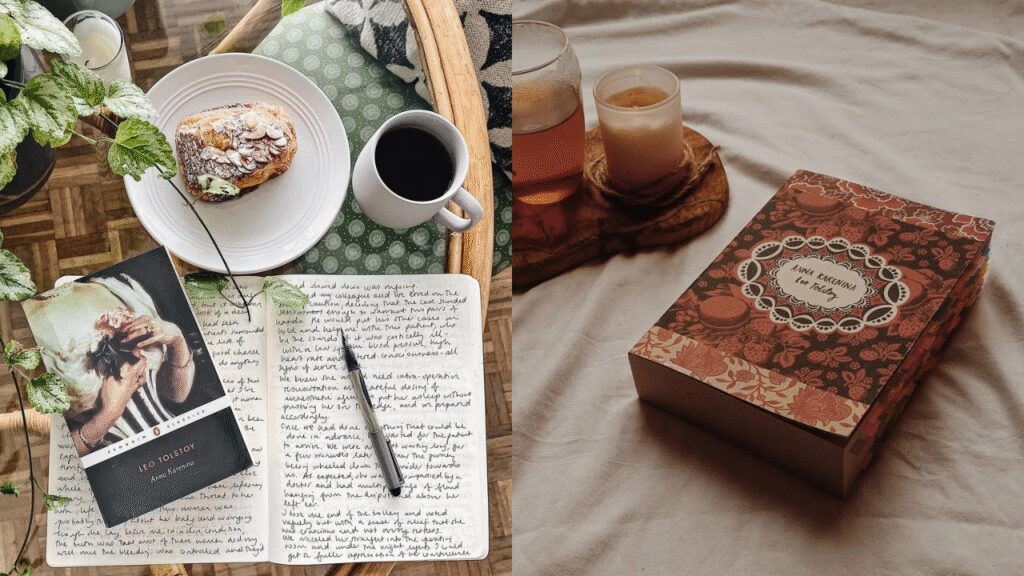

What ‘Anna Karenina’ Tells Us About Desire, Duty, and the Cost of Breaking Rules (Picture Credit – Instagram)

Few novels have entered the collective imagination with the force of ‘Anna Karenina’. First published in instalments between 1875 and 1877, Leo Tolstoy’s sweeping masterpiece is both a love story and a moral inquiry. Its opening line, “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way,” sets the tone for a work that interrogates not only romance but also society, responsibility, and the choices that shape a life.

For over a century, readers have been drawn into Anna’s world, captivated by her beauty, her vulnerability, and the daring choices that ultimately lead to her destruction. Beneath the melodrama of adultery and scandal lies a piercing examination of human desire and the weight of social obligation.

Desire As Liberation and Destruction

Anna’s passionate affair with Count Vronsky is one of literature’s most famous depictions of desire. Tolstoy shows love not as a gentle comfort but as a force both liberating and destructive. Anna, trapped in a loveless marriage with the cold, bureaucratic Karenin, seizes the possibility of happiness with Vronsky. Yet the intensity of their union isolates her from the stability of society.

In Anna’s yearning, readers see the eternal human struggle between what we want and what the world permits. Her choices expose how desire can free us from suffocating norms while simultaneously demanding sacrifices we are unprepared to pay.

Duty and the Shackles of Society

Tolstoy places Anna’s rebellion against the backdrop of a rigidly stratified Russia. The social world of salons, dinners, and horse races is not just a setting but a cage. Every character is measured against the expectations of class, family, and faith.

For Anna, the price of breaking her marital vows is exile from this society. She becomes an outcast, denied the company of respectable women and increasingly excluded from public spaces. Meanwhile, her husband, Karenin, embodies duty to a fault. His cold adherence to rules and appearances may preserve his reputation, but it leaves no room for compassion or human connection.

Tolstoy makes clear that duty can sustain social order, but when stripped of empathy, it hardens into cruelty. Anna’s tragedy lies not only in her affair but also in a society that cannot forgive her for it.

Parallel Stories and Moral Counterweights

While Anna’s story captures the imagination, Tolstoy balances it with the quieter life of Konstantin Levin, a landowner searching for meaning. Levin’s journey, rooted in the rhythms of the countryside and his eventual embrace of family life, offers a counterpoint to Anna’s storm of passion.

Through Levin, Tolstoy suggests that a meaningful life may be found not in defying rules but in aligning desire with responsibility. His search for spiritual and practical fulfilment is no less complex than Anna’s, yet it unfolds in harmony with duty rather than in rebellion against it. The novel thus holds a mirror to two paths: one of defiance and ruin, the other of compromise and stability.

The Cost of Breaking Rules

Anna’s downfall is not portrayed simply as punishment for her affair but as the tragic collision of private yearning and public judgment. Her despair deepens as Vronsky grows restless, as her ties to her son are severed, and as whispers of condemnation follow her everywhere.

Tolstoy does not present her as a villain, nor does he absolve her entirely. Instead, he paints her as deeply human, caught in a web of desire, pride, vulnerability, and societal cruelty. Her final act on the railway tracks is both horrifying and inevitable, leaving readers to wrestle with whether it was love, shame, or an unforgiving world that drove her there.

Why Anna Karenina Still Matters

The questions Tolstoy raised are as relevant today as they were in imperial Russia. What do we owe to ourselves, and what do we owe to others? How much freedom do we have to pursue happiness when bound by cultural and familial expectations?

Modern readers may live in societies that claim to value personal freedom, yet the tension between desire and duty persists in countless ways: in relationships, careers, and the expectations of community. Anna’s fate reminds us of the risks of living only for passion, but also of the costs of a world that denies forgiveness.

A Timeless Reflection on Being Human

‘Anna Karenina’ endures not because it offers easy lessons but because it resists them. It refuses to present love as purely redemptive, marriage as purely secure, or society as purely fair. Instead, it acknowledges the contradictions of being human.

Tolstoy’s brilliance lies in his refusal to pass judgment while compelling us to confront our own. To read ‘Anna Karenina’ is to sit with uncomfortable truths about love, loyalty, and the fragility of happiness.

Anna’s story does not end with moral clarity. It ends with sorrow, leaving us to fill the silence with our own reflections. Perhaps that is the greatest gift of Tolstoy’s masterpiece: the invitation to ask ourselves what rules we are willing to follow, and what desires we might dare to pursue.

For every reader, the balance between desire and duty is different. But Anna’s journey makes clear that whichever path we choose, the cost will be ours to bear.