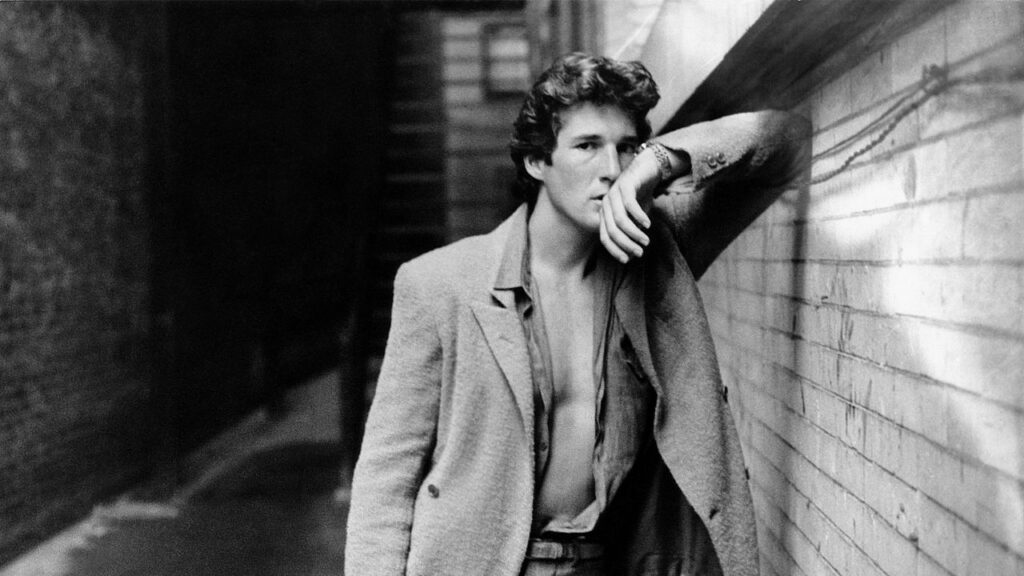

He haunted the sons before he haunted the fathers. That’s how it seemed to me. When American Gigolo came out in 1980 the louche, voluptuous landscape it depicted—the Polo Lounge; Perino’s; Westwood Village on a Saturday morning—was the one we all knew, just as we knew the cars (the convertible Merc Richard Gere drives in the film’s opening scene was the same one my dad had: a 450 SL), the drugs, and the sunlight. The suits, though. Those we hadn’t seen: Richard Gere’s suits—Julian Kay’s suits, since the sleek, semi-feminine (“Juli,” his pimp keeps calling him) nature of the character and of his clothes were as one—were new to us.

Our parents wore suits, of course. (“Our;” I’m talking about a small group of people here: the ones whose folks were Hollywood power brokers.) But those suits were boxy and brown. I’m working from memory here, of course, but my father bought his suits at Alandales in Beverly Hills. His designer of choice, then, was Zegna. Which is why Julian Kay’s Giorgio Armani suits—their softer colors (not brown but cream, tan, taupe, anthracite!) and looser, drapier cuts—were such a revelation. No teenager wants to dress like his father, and few teenagers (even in the high New Romantic era that was set to pop a year or two later) want to wear suits, but if it was possible to look like that . . .

Paramount Pictures/Everett Collection

It wasn’t, of course. Unless you were Richard Gere. But that wasn’t going to stop a lot of people from trying. People often misremember the eighties as Hollywood’s Armani Decade; they weren’t. Peak Armani wasn’t really achieved in Hollywood until the dawn of the nineties, as evidenced by this phenomenal CAA training video (come for the cameos by Ben Stiller and Sly Stallone, stick around for the appalling, uh, power ballad that refers to the agency as a “well-tuned Armani machine” while showing off one power-suited player after another.)

But Gigolo director Paul Schrader was ahead of the curve. He knew just how to do it, how to bend the disco excesses of the Hollywood seventies—the open collars, the jeans-with-jackets—into something supple and modern. Julian Kay had to travel between a world of rich people, wives of politicians and financiers, and a demimonde of pimps and rough trade: the suits had to travel with him, to change, as it were, with the light. Armani’s designs did that, just as they blew away the hirsute, aggressively “heterosexual” codings of the previous era—the Divorced Dad Casual of, say, Kramer vs Kramer or Starting Over—with something that felt equally flexible in terms of sexuality. They ended the seventies, it seemed, with a single stroke.