Ethan Hawke strolls in for our meeting in a small, crowded café in Brooklyn 15 minutes early. He lives nearby with his wife of almost 20 years, Ryan, and two children, and has come straight from a parent-teacher conference. (Hawke has four kids, between 14 and 27, two from his marriage to Uma Thurman.) “When you first have kids you don’t realize how impermanent it is,” he says. “I’m trying to not miss anything.”

He’s wearing a worn-in blue corduroy suit with a clashing pair of yellow striped sneakers, and if anyone in the room has recognized him, they haven’t made it obvious. He slouches coolly into a packed table between diners, with very little elbow room, and orders an Arnold Palmer and an arugula salad, grabbing at stray bits with his hands.

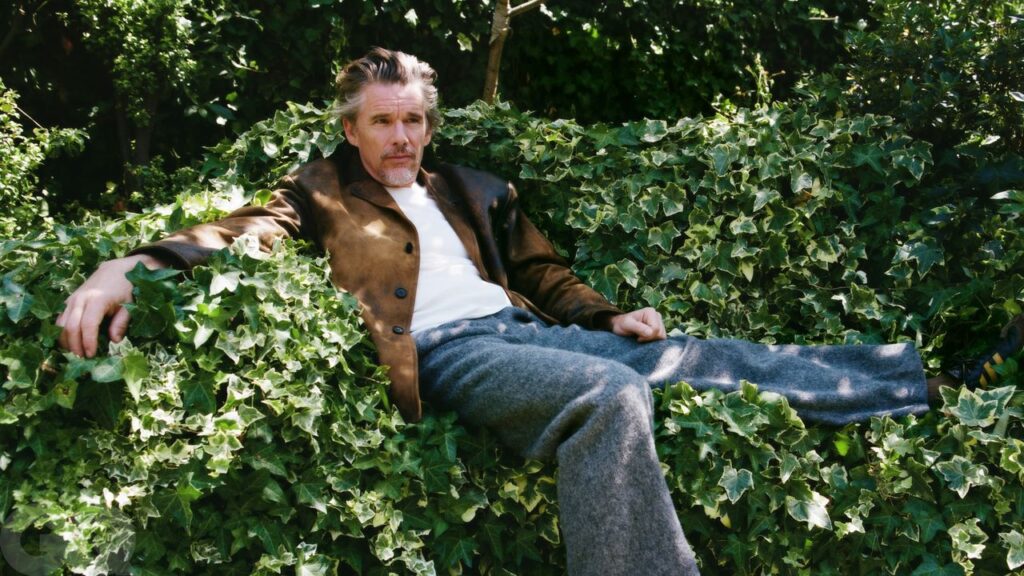

Hawke, now 54, has been hovering around the edges of fame since the 1980s, and you can see the passing of time in his face: the creases and lines in his forehead, the grey in his beard. But the eyes are still husky blue, the jaw just as chiselled as in his heartthrob days. Hawke first grabbed audiences’ attention in 1989’s Dead Poets Society, but it was 1994’s Reality Bites that turned him almost overnight into a symbol of grungy Generation X angst. “That was the moment that went from me being an actor to people knowing my name,” he says. “‘Oh, he’s one of those Dead Poets guys’ turned into ‘Oh, he’s him.’” The following year, he was on the cover of Rolling Stone, like cinema’s answer to Eddie Vedder.

But while others might have leveraged that heat into summer blockbusters and fragrance deals, Hawke spent his 20s and 30s poking around the edges of culture, writing novels, directing plays at the theatre company he cofounded, starring in Shakespeare on Broadway, and directing an independent film about the Chelsea Hotel. “Some people’s initial north star is to be fucking rich and have an airplane,” he says, his faraway gaze snapping into focus. “I was super interested in the people who made a real contribution to the arts.”

While not always a roadmap to box-office glory, Hawke’s penchant for picking offbeat parts has instead been a kind of syllabus for creative fulfillment, allowing him a discreet longevity that most actors would kill for. And it has, ironically, now made him the perfect star for the Letterboxd era, when teenagers excitedly log their favorite Luca Guadagnino movie and the $6 million Anora wins Best Picture over Dune: Part Two and Wicked. “I’m a believer,” says Hawke. “That can come off pretentious, but it’s so much better than being cynical. Cynicism kind of breaks your kneecaps.”

This autumn, Hawke is starring in three projects that show his range: showing his spooky side again as the villain in horror sequel Black Phone 2, dipping into prestige TV with berserk drama The Lowdown, and playing a 5-foot-tall Broadway legend in the sweet, sad Blue Moon, directed by his longtime collaborator Richard Linklater.

Linklater has now directed Hawke in nine feature films. They met one night in 1993 through a mutual friend, and ending up staying up chatting until 4.30 a.m.; afterwards, the director sent Hawke the script that would become 1995’s Before Sunrise, an eccentric little idea about a guy and a girl meeting on a train and spending an unplanned evening strolling around Vienna, talking about love and the meaning of life.