“], “filter”: { “nextExceptions”: “img, blockquote, div”, “nextContainsExceptions”: “img, blockquote, a.btn, a.o-button”} }”>

Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members!

>”,”name”:”in-content-cta”,”type”:”link”}}”>Download the app.

I’ll never forget the first time I saw someone drop back into Wheel Pose (Urdhva Dhanurasana) from standing. I was a student at the time, long before I completed my 200-hour teacher training, and I remember being both awestruck and mildly horrified at how her spine seemed to make the shape of a slinky.

At that moment, I recall having two seemingly opposing thoughts. How is that even possible without breaking your back? But also, I really want that to be part of my practice, too.

So I started working on my backbends. I focused on stretching and practicing as many backbends as I could think of each day. At the time, I thought backbending was all about flexibility—how deep you could go, how far you could curve, how much you could contort.

Although that idea might fly on Instagram, it doesn’t hold up in real-life teaching or long-term practicing.

Now, after guiding thousands of students through backbends in classes and teacher trainings as well as navigating my own low-back injuries and breakthroughs, I’ve learned that the secret to safer—and more sustainable—backbends lies in three unexpected but essential areas: strength, spaciousness, and breath.

How to Do a Backbend

When I began to understand the following and incorporate it into my practice, everything changed for me.

1. Strength: The Unsung Hero of Backbends

Most of us assume, as I had, that backbending is all about flexibility—how open are your chest and shoulders and how bendy can your spine be? But in my experience, the students who find the most ease in backbends aren’t the hypermobile ones—they’re the strong ones.

Bending backward places a significant amount of pressure on the spine. Without the support of engaged back muscles that act as the stabilizing force that lift and guide the body into a backbend, your body relies on passive structures—ligaments, joints, and the vertebrae themselves—to support your weight. That’s a fast track to unprotected compression and, over time, injury.

Although our bodies are designed to move into spinal extension, which is the backward movement that takes you into a backbend, the depth of extension that certain yoga poses demand exceeds what the average person can safely handle. That’s because so many of us attempt to come into these shapes without first building the strength needed to support them.

Over the years, I’ve had countless students share that their “low back just hates backbends.” Often, we’re drawn to the big, beautiful shapes—the Full Wheels and Camel Poses that flood our feeds—and we skip past the quiet, preparatory, and relatively boring backbends that lay the foundation for safe, easeful movement. But when we honor the body’s need to progress gradually, moving through increasingly challenging variations, something shifts.

Through well-sequenced classes that weave strength into flexibility, we learn to approach backbends by lifting and engaging through the muscles rather than collapsing into the joints. Over time, we begin to find freedom in the shapes, not just discomfort.

Try This: Building the sort of strength needed in backbends happens by incorporating upper back, back body, and core work into your classes—and that often means practicing poses that aren’t backbends.

Practicing proper alignment in Plank Pose and Chaturanga builds deep core and shoulder girdle strength. Spending time in Chair Pose (Utkatasana), especially when cued to sit your weight back so the glutes and hamstrings fire up, can strengthen the lower body. Similarly, static holds in Pyramid Pose (Parsvottanasana) strengthen the hamstrings by requiring them to activate and provide stability while lengthening. You can also rely on Warrior 3 (Virabhadrasana III) and Half Moon Pose (Ardha Chandrasana) with a strong, active pressing action through the lifted heel to wake up the entire back body.

And for teachers, including a Baby Cobra variation in the warm-up of a backbending class is a great way to illustrate the engagement in the upper back. Cue students to lift just the chest while floating the hands off the mat, keeping the glutes relaxed and the movement subtle. This helps build awareness of and activation in the thoracic spine without relying on the arms to find the lift.

Layering these movements throughout your practice and teaching builds the strength and support system needed for backbends to feel safe, lifted, and integrated.

2. Space: Lengthen Before You Bend

One of my favorite ways to help students visualize what backbends are trying to accomplish in the body is to have them imagine the spine as a garden hose. If you try to sharply kink it in one spot, you’ll create pressure and block the flow. But if you lengthen the hose before attempting to bend it and gradually arc the hose, the curve happens more naturally and becomes much less damaging.

The key to creating this arc is to focus on lengthening the areas of the body that surround the spine—primarily the muscles along the side body and across the front of the hips. This helps distribute the work of backbending throughout the body rather than dumping it solely on the spine.

It’s important to note that when the side body is compressed, the action from backbending has nowhere to go but into the low back. When you create space from the waist all the way to the armpits, you free up the spine to extend more naturally without forcing the curve from a single area. This expansion shifts the effort away from only the lumbar spine and into a more balanced and supported shape.

Try This: So whenever a student asks how to work on Full Wheel, my first recommendation is to focus on any poses in which the arms move over the head, including Warrior 1 (Virabhadrasana 1), Upward Salute (Urdhva Hastasana), Extended Side Angle (Utthita Parsvakonasana). Can they bring awareness to the lift and lengthening that needs to be created in the side body? It might not happen in a single class, but over time, the body will open in the places needed to support the deepening of backbends.

A focus on side body lengthening also allows you to find more focus and creativity in your ordinary practice. Suddenly familiar poses such as Tree Pose (Vrksasana) and Triangle Pose (Trikonasana) can be observed through an entirely new lens. Bringing this type of awareness to your practice and teaching makes it easier to be curious about and find the actions of the side ribs moving. When it’s time to practice the bigger backbends that come later in a sequence, the result is almost always more space, more ease, and less pinching.

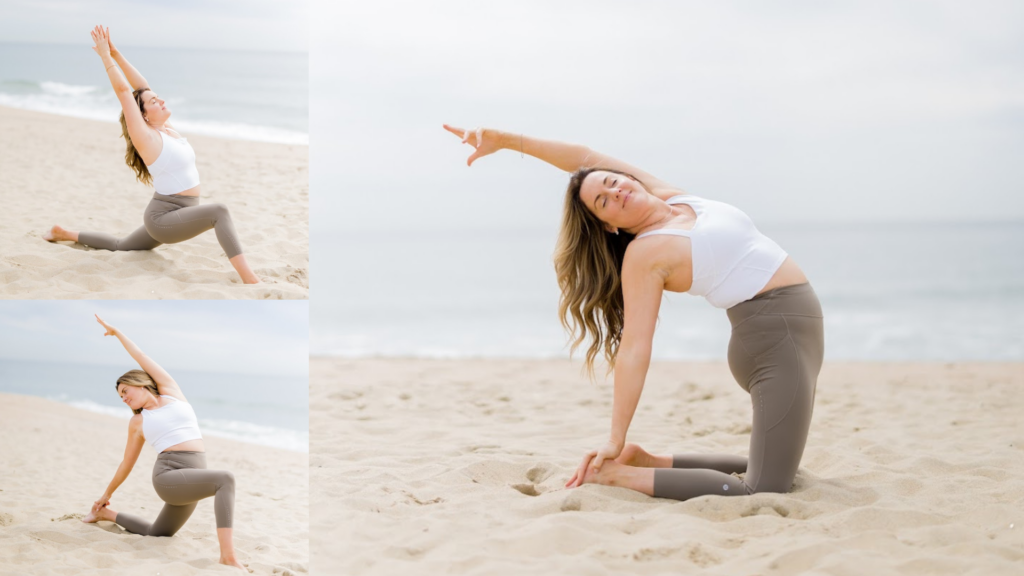

And when you’re practicing or teaching mild backbends—think Low Lunge (Anjaneyasana), Cobra Pose (Bhujangasana), and Warrior 1—emphasize upward lifting before you arc backward. Teachers, try using language like “lengthen through the sides of your waist” or “think about sending your chest and collarbones up and then back” to invite more space before attempting the backbend.

Creating this kind of length isn’t about making the shape bigger—it’s about making it more integrated. And when you lead with space, the shape becomes not just safer and more accessible but filled with a sense of freedom and ease.

3. Breath: Let It Lead the Way

I’ve heard people say that if you’re not focused on the breath in a yoga class, then it’s no different than a gym class. It’s true, breath is integral to any yoga practice, and nowhere is that more obvious than in a backbend.

When people practice a challenging backbend, the breath is often the first thing to go. The nervous system goes on alert, the muscles of the rib cage and diaphragm tighten, and suddenly the body is holding on instead of opening up.

But when we breathe with the shape, using the breath as a guide to help find softness within steadiness, it becomes the bridge between effort and ease.

When I was leading a 300-hour YTT group through backbends a couple years ago, we discussed how to know when students are ready to try an intense variation of a pose, such as One-Legged Wheel Pose (Eka Pada Urhdva Danurasana). What we eventually landed on was allowing students space to observe their breath before offering them the option to attempt the variation. Because how many students are breathing deeply for three to give breaths in Full Wheel? If freedom of breath isn’t there, then maybe it’s not time to move to an even more challenging variation just yet.

The breath being the main indicator of whether it’s time to move toward rest or more effort wasn’t something I had previously considered. But after that conversation, I began to offer it as a way for students to do a pulse check on which choice they should make for their individual practices. It worked.

Keep in mind, students can be cued to use the breath not just to get into the pose but also to deepen, explore, and exit it. The inhalation creates lift and space. The exhalation grounds and steadies. The continued cycling between them helps you stay present with all the sensations along the way. Together, they create a rhythm that can make even intense backbends feel nurturing.

Try This: When practicing or teaching backbends, cue or think of the breath as a primary action and not just a side note. For example, “Use your inhale to help create space in the side body as you lift up.” Or “Use your exhale as you press through the soles of your feet to find stability at your base.”

Encourage yourself or students to find a sustainable breath pattern the entire time they remain in a shape, even if that means easing off a little on the depth.

Bonus: Inhale Courage, Exhale Control

There’s one more aspect of backbending that can make it challenging, and that’s the fact that there can be something inherently vulnerable about coming into backbends. These poses ask us to expose the entire front body, which we’re evolutionarily wired to protect, and to let go of guarding long enough to trust ourselves as we bend backward into the unknown. That can bring up unknown resistance, fear, and feelings of vulnerability.

And that’s exactly what makes backbends so potent.

The more I practice and teach yoga, the more I realize there isn’t just one hack or quick-fix to safer backbends. It requires a shift in perspective about taking a more intentional approach. It’s understanding that these poses aren’t about forcing a shape or checking a box. They’re about inviting strength, creating space, and staying connected to the breath.

When approached in this way, backbends become less of a performance and more of an open conversation between the body, mind, and breath. Whether you’re teaching a packed vinyasa class or simply trying to make peace with Locust Pose (Salabhasana) in your own practice, these principles will forever change how you approach backbends.

So the next time you roll out your mat, maybe ask yourself, What would it feel like to move into a backbend from a place of curiosity rather than ambition? What if, instead of chasing depth, I chose integrity? What if your most powerful heart opener wasn’t the deepest but the one that felt like home in your body?