Published November 5, 2025 05:30AM

In late October, a group of staffers at Yosemite National Park stopped by a maintenance building within the park to visit some of their coworkers. They brought stir-fried chicken thighs, pumpkin soup, and home-made pumpkin spice muffins. This was a few days after they had delivered lasagna to Yosemite’s law enforcement building, and chicken masala to maintenance staff.

An NPS worker, who we will call Robert, told Outside that the recipients of the hot meals were surprised and grateful. While many of Yosemite’s employees have been furloughed amid the federal shutdown, some jobs like law enforcement and maintenance staff are having to work their usual shifts—even though they have not been paid for two pay periods.

“The food isn’t putting money into anyone’s account, but it’s a way to keep morale up and let people know we are in it together,” Robert told Outside.

The food, Robert said, was paid for by the National Federation of Federal Employees (NFFE), a major labor union that represents government workers across multiple branches. Earlier this year, NPS workers at both Yosemite and Sequoia-Kings Canyon National Parks voted to join the union. Now, NFFE is helping those workers get hot meals. The union is also informing workers about when they might get paid and how to preserve their employment rights, even as the White House declares its intention to fire more park service workers.

Throughout September and October, Outside spoke to five sources at the National Park Service (NPS) about unionization efforts within the agency. Outside granted these sources anonymity, as the NPS has forbidden its employees from speaking directly to journalists.

Outside also reached out to the National Park Service for comment on the unionization efforts at some parks. We received a bounceback from the main NPS media page: “Due to the lapse in appropriations, I am out of the office and not authorized to work during this time. I will respond to your messages when I return.”

When Robert and the more than 600 workers at three California NPS sites voted to unionize in August, they joined thousands of other federal workers being represented by some nine separate unions. Now, more than 40 different NPS units—ranging from Saguaro National Park in Arizona, to the Blue Ridge Parkway in North Carolina, to Gettysburg National Military Park in Pennsylvania—are unionized. Union reps told Outside that as many as 100 other national park units are preparing to follow their lead.

This labor movement is being put to the test by the Trump administration’s cuts and rollbacks. Even before the government shutdown thinned the ranks of working national park staff, the White House had bled the park service of a quarter of its staff through layoffs and buyouts. The administration has also canceled the collective bargaining agreements that unions had forged with multiple federal agencies. It’s an assault on organized labor that legal scholars call unprecedented, and will put the unions’ organizing efforts to the true test.

August’s unionization vote in Yosemite and Sequoia-Kings Canyon made international headlines. The NFFE had been trying to organize workers at those parks for two years with little success—until NPS workers were galvanized by the administration’s cuts throughout the winter and spring.

“Morale is pretty poor,” said Genny, an NPS worker at the agency’s headquarters in Washington D.C. A member of the Resistance Rangers, a network of current and former NPS workers who have spoken out against the recent federal cuts, Genny is a union president for the National Treasury Employees Union, which also works with NPS workers.

“Most of us signed up to work for a mission and on a set of goals, about protecting and preserving places and stories, and that is a very difficult mission to fulfill right now,” Genny said.

Union members cited a range of reasons for the malaise: the reduction of the park service workforce beginning shortly after the Trump Administration took office in January, a hiring freeze that led to scientists cleaning toilets during the busy summer season, and a proposed slashing of the park service budget by $1.2 billion.

That’s on top of the traditional challenges faced by park service workers: low pay and dilapidated living quarters. In Yosemite, employee housing has been linked to dangerous hantavirus infections. “We’d like to talk about the ants in the walls, the decks that are falling apart,” Robert said. “We are making $18 an hour to live in this, but we can’t say anything or we’d be fired so fast our heads would spin.”

Robert said that government workers were being placed on leave at other federal agencies for speaking out, as well as his co-worker at Yosemite, who was let go for hanging a trans pride flag on El Cap.

Better housing and other working conditions are something that park service union members are counting on their organizations to secure for them, especially as they cannot bargain with the agency for better pay. Congress alone can set pay for government workers, and federal law dictates that it’s a felony to go on strike.

After voting to unionize, federal workers negotiate a collective bargaining agreement with the federal agency they work for. But unlike in the private sector, these contracts cannot determine salary. Rather, the agreements oversee terms such as work-from-home policies—they also create a structure for handling disputes between workers and managers.

A worker we will call Seth, a 23-year park service veteran, told Outside that workers often go to the union when they feel they’ve been cut out of overtime or hazard pay, or fired without just cause.

He also told Outside about a situation in 2004 that was solved by the union. Managers met behind closed doors and decided to eliminate Seth’s division.

But a union rep got wind of the action and disputed it, arguing that the union had not received proper notification of the meeting—an unlawful action according to the collective bargaining agreement. Supervisors backed down and the department was saved, Seth said. “I joined the union the next day,” he added.

In 2021, a union dispute erupted when five NPS trainers had their jobs terminated shortly after they were relocated to the Grand Canyon’s Albright Training Center. The National Treasury Employment Union, the union that took on the battle, proved that the management had retaliated against the trainers because they were part of a union. The NTEU won a $350,000 settlement for the five.

Sources told Outside that many NPS managers are sympathetic toward unions and the workers who belong to them. Brad, a nine-year veteran of the NPS, said that many managers have risen through the agency ranks and understand the austere conditions that NPS workers endure.

“Most of the things people want to negotiate for are to better enable them to do their work safely, effectively, and efficiently,” said Brad. “Better morale and safer working conditions mean people stay in their jobs longer and so we have a more experienced, more professional workforce.”

Labor unions can also lobby Congress to improve working or living conditions or for increased hazard pay for federal workers. The NFFE recently did this on behalf of wildland firefighters, eventually helping draft the Wildland Firefighter Hazard Pay Correction Act (H.R. 5091), which was introduced to Congress in September, 2025.

Unions can also reach out directly to the press and the public to generate support for their members, something the organizations have been doing a lot since Trump’s inauguration.

Still, the vast majority of the National Park Service’s 433 units aren’t unionized, sources told Outside. There are several reasons for this, sources said. NPS salaries are low, and union dues range between $17 and $35 per paycheck. Many NPS workers are seasonal, which gives unions less time to recruit them.

A third reason is simple geography. “We tried to organize the Grand Canyon a few years ago and didn’t get anywhere,” Seth said. “It was just really difficult to get meetings together.”

Many park service units, Brad points out, are spread out over hundreds of miles. “Some of them have just a few eligible people,” he said. “Lots of people living and working deep in the backcountry with no cell reception.” Many of the NPS workers who are unionized are based in Washington D.C, where there’s a greater concentration of year-round employees.

A final reason for the lack of unionized NPS units, sources told Outside, is the common idealism amongst park service workers. Some NPS employees don’t want to take a stance against the agency, sources said.

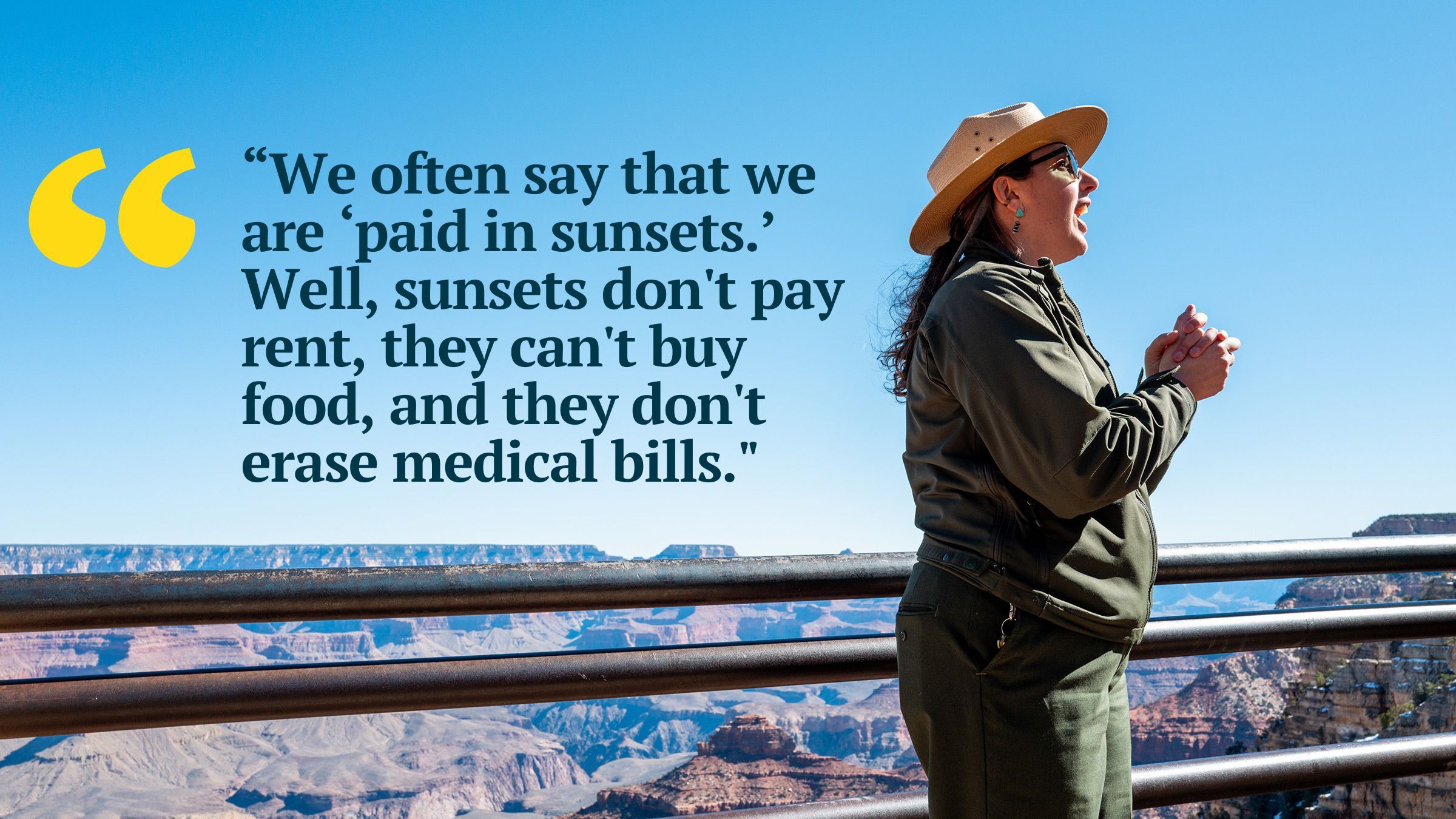

“Park service workers often feel very privileged to have the jobs they do,” Brad said. “All of these places—from the big national parks to the smallest historic sites—are national treasures, and it is an honor and a privilege to dedicate my life to preserving them.”

The drawback, Brad said, is that the NPS can get away with offering low pay and subpar living conditions. “We often say that we are ‘paid in sunsets.’ Well, sunsets don’t pay rent, they can’t buy food, and they don’t erase medical bills,” he added.

But the Trump administration’s attacks on NPS workers may prove to be a turning point for the labor unions. Sources told us they expect to see more units vote to adopt collective bargaining agreements.

“A lot of people who weren’t unionized before are asking questions,” said Collin, a NPS worker and union representative. “I’m fielding a lot of calls now.”

Collin and other sources told Outside that workers at as many as 100 national park units are moving towards unionization. Sources declined to say which NPS units are considering the move.

In March, President Trump signed an executive order that directed 22 federal agencies to ignore their union collective bargaining agreements. Those agencies include the IRS and the EPA. The NPS was not listed. Unions are fighting the order in court.

“This is the most significant assault on collective bargaining rights we have ever seen in the United States,” said Randy Erwin, president of NFFE, in a press release. The NFFE filed a lawsuit in April to challenge the order alongside six other government-employee unions. “It is clear that this executive order is retaliation for federal unions fighting back against the Trump Administration’s attempts to dismantle the civil service,” he added.

The unions have also filed suits to push back on the White House’s attempts to fire furloughed workers. As of October 31, a federal judge continued to block those firings, which could include 270 NPS positions.

Michael Duff, a unionization expert and professor at the St. Louis University School of Law, expects that ruling to be appealed. Duff predicts that one or more of the dozens of lawsuits the federal unions have filed on behalf of their collective bargaining rights will make it to the Supreme Court this year. That will determine whether unions can continue to fight for the rights of federal workers.

“The executive branch has had struggles over expanding and curtailing union activity for federal workers for more than a century, usually along party lines,” said Duff. “But this is the pinnacle.”

Union members in Yellowstone, Yosemite, and Sequoia National Parks have yet to sign collective bargaining agreements with the NPS. That process can take anywhere from three months to two years, and no progress is made during a government shutdown.

That hasn’t stopped the unions from offering their members the moral support of food drives, as well as bulletins explaining their rights amid the shutdown. “The NPS gave us no guidance until practically the day of the shutdown, and even the guidance issued on how to fill out timesheets was changed after we left,” Brad said. “Meanwhile, unions have compiled a series of documents that provide real guidance and advice for employees.”

Rober said he has been studying the documents that the NFFE sent him and other Yosemite workers. The handouts, free meals, and support, he said, has improved his morale.

“You feel like it’s not just you against the government now,” he said. “You feel like the other thousands of people in the unions have your back.”