As Japanese Walking takes off online, it’s worth asking: Why did 10,000 steps become the global standard for health? Was it ever based on science? Not exactly—and here’s the step count we should actually be aiming for.

(Photo: Fitness watch on hand: simplehappyart/Getty; Design: Ayana Underwood/Canva)

Published October 7, 2025 03:00AM

A few years ago, in 2020, during the pandemic, I started exercising in the only space I had: my living room. No gyms. No studios. Just a yoga mat and free YouTube workouts.

Over the course of a year, I lost 100 pounds—weight I’d carried most of my life. The change is the result of a gradual layering of habits—first a high-protein diet, then online workouts, followed by walking and running, and eventually intermittent fasting. But the real transformation wasn’t just physical. Somewhere along the way, I built something harder to measure: a healing relationship with movement. For the first time, exercise wasn’t about shrinking. I was expanding into myself.

Eventually, I took that newfound confidence outside. I dreamed of being one of those amateur runners crossing the Boston Marathon finish line while the city collectively thawed from another long, gray winter. There was just one problem: I hated running. The poignant burn of shin splints. The sharp gasps for air. The way my lungs felt like they were being folded into origami. It was clear that no matter how badly I wanted to become a runner, my body wasn’t on board.

But walking? Walking was having a cultural moment—digital creator Mia Lind was actively promoting her now-famous Hot Girl Walk—and I was more than ready to hop on that bandwagon. I bought ankle weights (these two-pound weights are my favorite), mapped out a 2.5-mile loop, and walked every day.

I used to think of walking as a consolation prize—the thing you did when you couldn’t run. I couldn’t imagine going from an 8:10 pace to genuinely enjoying what felt like a 24-minute mile—the kind of slow movement where my Apple Watch buzzes to ask me if I’ve stopped moving.

Fast forward to May of this year, and a new walking trend has captured our attention: Japanese walking. In a viral video, fitness coach Eugene Teo explains this method of interval-style walking, which involves alternating between walking fast for three minutes and walking slow for three minutes, for five sets in half an hour. The goal? Metabolic efficiency.

I used to believe walking only counted if I hit 10,000 steps a day. But over the past few years, as walking has shifted from a cooldown to the centerpiece of the wellness conversation, I’ve realized that isn’t true.

10,000 Steps a Day—the Rule We Didn’t Question

Before I ever mapped out my walking loop, I thought 10,000 steps was a rule. Not a suggestion.

It lived everywhere: embedded in my fitness tracker, baked into my phone’s health app, echoed in friends’ attempts to “close their rings.” It felt like the adult version of eating your vegetables. You just did it.

But here’s what no one tells you. Ten thousand steps didn’t come from science. It came from a pedometer ad.

In mid-1960s Japan, amid a national fitness push ahead of the 1964 Tokyo Summer Olympics, exercise physiologist Yoshiro Hatano estimated that doubling the average person’s daily steps—from about 4,000 to 10,000—“would result in an increased energy expenditure of about 300 kcal/day.” There were no clinical trials. No test subjects. Just back-of-the-envelope energy math.

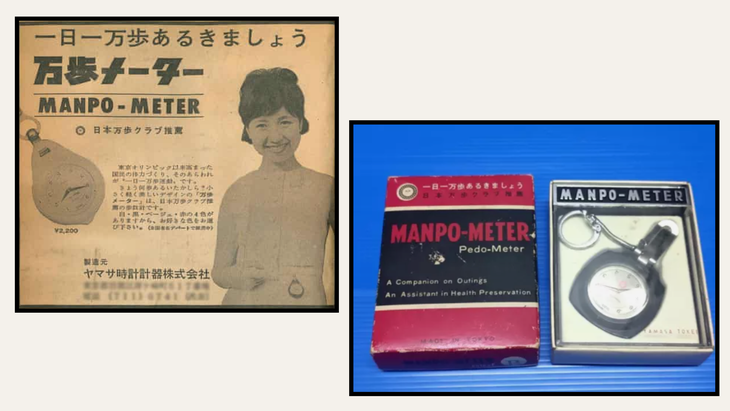

Around the same time, Yamasa, the company known for its delicious soy sauces, released a pedometer called the manpo-kei (万歩計)—which literally translates to “10,000 steps meter.” The number wasn’t precise. But it was motivational, and so it stuck.

In the 2015 book Health Trackers: How Technology Is Helping Us Monitor and Improve Our Health, technology journalist Richard MacManus describes how Japanese companies, such as Coca-Cola Japan and the green tea brand Ito En, distributed pedometers as part of large-scale marketing campaigns. These giveaways weren’t just promotions; they reinforced 10,000 steps per day as a public health guideline, embedding it into daily routines and branding it as common sense. What began as a marketing device was quietly becoming a cultural standard.

That foundation set the stage for one of Silicon Valley’s most iconic inventions—the FitBit. When Fitbit launched in 2009, it put 10,000 steps as the default daily goal—not because medical science required it, but because decades of repetition had already made it feel official. Fitbit’s own Help Center confirms: “The default daily step goal is 10,000 steps.”

Other wearables—like those from Apple, Garmin, and Samsung—gave steps prominent placement, even when their dashboards focused more on metrics like calories burned or active minutes. By then, steps had become the clearest, most shareable proof of progress.

The Quiet Resistance Embedded in Japanese Walking

The 10,000-step rule didn’t begin as a mandate; it started as a story—a round number, wrapped in optimism. Like most stories, it’s worth asking, What happens when you stop believing it?

That question is what led me to try Japanese Interval Walking.

At first glance, it appears to be just another niche trend. But the more I read, the more it felt like quiet resistance—a method grounded in rhythm, not accumulation—a counterpoint to Western fitness culture.

The Benefits of Japanese Walking, According to Science

In 2007, exercise physiologist Dr. Hiroshi Nose and his team at Shinshu University in Japan developed Interval Walking Training (IWT), a deceptively simple yet highly effective protocol specifically designed for aging populations. Walk fast, then slow, three minutes each, five times per walking session, at least four days each week. No wearables. No tracking apps required.

In a five-month randomized controlled trial involving 246 older adults, IWT outperformed moderate-intensity continuous walking and sedentary control groups. Participants in the IWT group experienced a ten percent increase in peak aerobic capacity (VO₂ max), as well as a 13- and 17-percent increase in quadriceps and hamstring strength, respectively. A reduction in systolic blood pressure was another benefit.

Broader reviews associate IWT with significant gains in fitness, muscle strength, and glycemic stability in individuals with type 2 diabetes.

Japanese Walking Focuses on Effort, Not Step Count

What surprises me most is how differently IWT frames the idea of progress. It’s not about pushing harder, going longer, or obsessing over streaks. Instead, IWT asks for attention, not intensity; presence, not performance. You don’t need to post your workout stats or chase medals. You just need to show up, breathe a little harder, and let your body remember how to adapt.

It’s not about what you can post—but how you feel when you’re done.

That philosophy sits in sharp contrast to step-count culture, where success is visible, measurable, and shareable, where the end goal is often less about how your body feels and more about whether your tracker vibrates in approval.

Of course, IWT isn’t a magic bullet. The Shinshu University training method focused on a fairly specific group—healthy, older Japanese adults—which makes it harder to say how the protocol translates across more diverse populations.

But here’s the encouraging part, per the Shinsu study: even when participants didn’t hit every target, they still saw meaningful gains in blood pressure, aerobic capacity, and strength. In other words, you don’t have to be perfect for IWT to work—you just have to show up often enough.

In a culture that equates health with hustle, that quiet efficiency is the most radical act of all.

But structure isn’t the only way intention can take shape. While some walks are designed for blood pressure management, others are curated for presence and joy. If IWT is a quiet rebellion against numbers, the Hot Girl Walk is a bold reimagination—and both challenge what progress is supposed to look like.

How Many Steps Should You Walk Every Day?

Because walking stopped being something you did and evolved into something you tracked, shared, and proved, step count signaled effort, discipline, even virtue.

And yet, the number was never required. It turns out that you don’t need 10,000 steps to be healthy. Not even close, in some cases.

A 2020 study in JAMA Internal Medicine found that for older women, health benefits began to appear around 4,400 steps and plateaued at 7,500 steps. A 2022 Lancet meta-analysis found that 6,000 to 8,000 steps were adequate for most older adults, with younger adults typically plateauing closer to the 10,000-step count. A 2024 review showed even 3,000 daily steps offered some protection against early mortality and heart disease.

So why does the 10,000-step rule endure? Because it feels complete.

Behavioral psychologists refer to this phenomenon as the “round number effect”—our instinctive attraction to clean, whole figures. Buzzes, badges, and streaks turned it into more than a goal. It became proof of doing wellness right.

But when the number becomes the focus, quality is often lost. A leisurely 10,000-step stroll might do less for your heart than 4,000 brisk ones—but your app rewards both the same.

The more I walked, the more I realized the act itself is simple—but the meaning we attach to it rarely is.

For some, walking offers structure. A measured, repeatable ritual. For others, it’s a mood, an aesthetic, a way to step into confidence. And for many, it’s just a number—a goal preloaded into a wristband, quietly urging us to try harder. Each of these approaches reflects not just a style of movement, but a worldview. A belief about what counts. What’s worth tracking? What progress looks like.

These paths don’t compete so much as coexist. But they do ask different things of us. Some ask for precision. Others, presence. Others still, proof.

For me, the meaning of walking didn’t arrive all at once. It unfolded slowly—on cold mornings, on sidewalks slick with slush, through half-smiles exchanged with strangers I’d never know by name. In moments when no one was watching, and I wasn’t performing.

What started for me as a 2.5-mile loop with ankle weights and a podcast became a daily invitation: to listen to my body. To loosen my grip on old goals. To move for the sake of moving, not for the data I could collect or the image I could project.

That shift didn’t erase ambition or discipline—it redefined them. It reminded me that movement doesn’t have to equate to an arbitrary round number to be meaningful. It doesn’t need to be validated by a graph or broadcast in an Instagram caption.

Sometimes, the most radical thing you can do is move without trying to make it count.

Want more Outside health stories? Sign up for the Bodywork newsletter. Ready to push yourself? Enter MapMyRun’s You vs. the Year 2025 running challenge.