A easy-to-understand guide to going father and staying safer while saving money

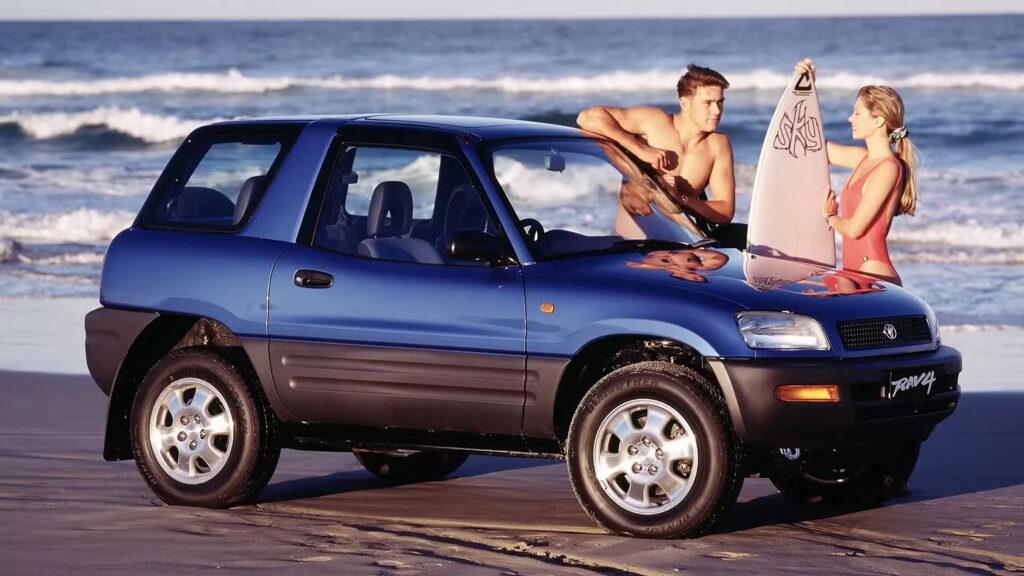

(Photo: Toyota)

Updated September 16, 2025 03:53PM

It doesn’t matter what you drive, the only part that touches the ground is the tires. And that means components like your 4×4 or AWD system, brakes, and motor are only as good as the tires they work through. Let me make it easy for you to understand which tires are right for your vehicle, and the conditions you drive through.

Why Not Just Keep Things Stock?

The tires that come on new cars aren’t always chosen for how they’ll perform in real life. Automakers have long been under pressure to hit strict fuel-economy targets, with huge fines if they fall short. One of the easiest ways to squeeze out a little extra efficiency in government tests is by equipping cars with tires like the ones you see typically come with new cars. But those gains are tiny. In the real world, they’re usually wiped out by traffic, weather, terrain, or simply the way people drive. TL;DR: stock tires are often designed to help carmakers pass a test, not to give you the best performance on the road.

Is There Such a Thing as One Tire That Can Do Everything?

No. Every tire is a compromise. If you want to boost rain performance, for example, one of the things you’d do is increase the percentage of silica versus natural rubber in the tire’s compound. But the higher the silica content, the greater the propensity for damage when driving on gravel or rocky surfaces, so that very good rain tire will wear very rapidly if used away from paved roads.

Each tire has a specific set of circumstances in which it’s designed to work best and a type of vehicle it’s designed to work with. The burden is then on you to match a tire to the conditions you encounter most frequently.

For many drivers, the answer is not a single tire. If you drive in places that experience winter conditions, you need to run a tire designed to perform in extreme cold and on surfaces as varied as slush, snow, and bare ice. Advancements in rubber compounds have given modern winter tires unbelievable amounts of grip on hitherto slippery surfaces, but those same compounds will rapidly wear out in above freezing temperatures. So it doesn’t make sense to leave winter tires on during summer months or if you’re driving to a warmer climate.

Conversely, tires designed to last many miles, or perform well in above freezing temperatures, are unable to deliver safe grip below freezing or on slippery winter surfaces. Drivers who tackle both need two sets of tires, which they should switch out late each fall and early spring, or before any trip to a place with different weather.

How Tires Are Made

Starting from the inside out, a tire’s strength is provided by its carcass, a meshwork steel or synthetic fibers. Decades ago, before the advent of modern material technologies, tire carcasses were made from cotton canvas. To make a tire stronger, additional layers of canvas (called plies) were added. You can still find those referenced on modern tires today, with their weight capacities listed in “ply equivalents.” (I explained them in detail back in 2021 as part of a deep dive into all-terrain tires.)

A carcass designed to support less weight will be more flexible and require less air to achieve proper inflation. A carcass designed to support more weight will be less flexible and require higher air pressure. A more flexible tire will provide more grip and better ride quality, and changing the weight capacity of the tires on your vehicle will require you to use different pressures than those listed in your vehicle’s owner’s manual.

A tire’s tread and sidewall are made by compounding natural and synthetic rubbers with chemicals, like sulfur and carbon black. This is where most of a tire’s performance is achieved. Different performance metrics, like what kinds of surfaces a tire can grip or how many miles it’ll last, are achieved in the compound. This can make visually assessing a tire difficult, since all you see is black rubber.

That rubber compound and carcass are then combined in a mold, which also forms the shape of the tire’s tread and sidewall. The deeper the tread (typically expressed in fractions of an inch), the better its pattern will grip loose surfaces and clear standing water. Tread depth also indicates how much rubber has been applied to the carcass. The thicker the rubber, the more miles it will last and the better the tire will be at resisting punctures.

The pattern in which a tire’s tread is molded is also determines how it can clear water or mud, hang onto snow (the best material for gripping snow is more snow), and mechanically key with off-road surfaces. More open patterns also tend to be noisier, as they catch more air as they spin.

Performance is a combination of all those factors: the carcass’s flexibility, the chemical properties of the rubber compound, and the pattern and depth of the tread.

Decoding the Sidewall

How do you determine if a tire is designed for your vehicle, and the conditions in which you plan to drive? Every tire tells you that exact information, right on its sidewall. There’s a lot of information on a tire’s sidewall; here’s what’s most important to drivers of normal cars, crossovers, trucks and SUVs, who use their vehicles on and off-road and in winter weather.

Tire Size

The first and most important piece of information is the tire size. On passenger car tires, these will be expressed in metric form, with a size like 265/70R18: “265” is the tire’s width in millimeters and “70” is the tire’s aspect ratio—or the height measured from the outer rim to the tread, as a percentage of its width. The “R” stands for radial, and is a type of carcass now universal. The “18” is the diameter of the wheel the tire is designed to fit.

On some larger trucks and 4x4s, you may find the tire size listed in imperial measurements. Those will read something like 35×12.5R18. These are much easier to read, with 35 being the tire’s outside diameter (in inches), 12.5 being its width, and 18 its wheel diameter.

In almost all cases, you’re going to be best off sticking with this stock size, or something very close to it. Sometimes a minor change in tire size of only a few millimeters will net you a greater variety of choice, or lower prices. This online tool will help you compare sizes. If you are modifying your 4×4 to prioritize off-road performance, I wrote about choosing upsize tires and the formulas you need to calculate their performance in this piece, a few years ago.

Date Code

Then, there’s the tire’s date code. Tires are designed to last six years from their time of manufacture. Beyond that date, tires can begin to experience invisible damage that may lead to sudden and total failure. Running old tires risks your life, as well as those of your passengers and other drivers.

You’ll find the tire’s date of manufacture in the last four digits of its DOT code. Just look for the letters “DOT” on a tire’s sidewall, then skip to the last four digits in the series of numbers that follows it. The first two digits there will be the week (of 52) in a given year when that tire was made, and the last two digits are the year. So, “4623” means the tire was made on the 46th week of 2023, and it’ll be safe to run that tire until November, 2029.

Load Rating

On passenger car tires, load rating is listed as a three-digit number. On light truck tires, it’s a letter, running from A to F. It’s all a bit complicated, and you’re probably better off using your smartphone to look up the tire’s spec sheet on its manufacturer’s website, where its load is listed as a plain number of pounds.

That data is mostly relevant if you’re planing to tow a heavy trailer or try and carry a heavy camper. But, it’s also relevant information in that you want to match a tire’s load rating as closely as possible to your vehicle’s gross weight rating. Running too strong a tire will impair ride quality and grip.

Much more easy to decipher are pictorial sidewall stamps, some of which include:

- All-Season: These are the cheapest possible tires, with the least possible performance. They begin to lose grip even on dry pavement as temperatures fall past 45 degrees Fahrenheit. If your vehicle is equipped with these, replace them at the earliest possible opportunity.

- M+S: This stands for “mud and snow” and indicates that a two-dimensional representation of the tire’s tread pattern contains at least a 20:80 ratio of void to lug. No physical test of a tire’s performance is conducted, and this stamp does not guarantee that a tire will perform safely in mud or snow.

- Three Peak Mountain Snowflake: This indicates a test has been performed in which the tire has demonstrated at least ten percent superior acceleration traction on packed snow compared to the industry’s Standard Reference Test Tire (SRTT). The SRTT is loosely equivalent to the cheapest possible all-season tire from a decade or more ago; ten percent is not a significant advantage, and packed snow is far from the only slippery surface you’ll find in winter.

- Ice Grip: A new symbol that began rolling out on tires in 2023, this indicates that a tire has passed a test in which its braking distances are at least 18 percent shorter than the SRTT on bare ice. This is the only sidewall stamp that indicates a tire will be safe to use in winter conditions.

Common Tire Mistakes

In addition to selecting a tire, you need use it correctly. Avoid these common pitfalls to get the most from your tires.

1. Not Calculating Correct Pressures

Air pressure inside the tire is what supports the weight of your vehicle. As you add load in the form of cargo, a camper, a trailer, or anything else, the weight your tires need to support increases, and with it the pressure in your tires. The same is true as you fit larger tires or ones with higher load ratings. Failing to calculate the right pressures can cause disappointment when people change tires and experience poor or unpredictable handling. Here’s where to calculate the correct pressure.

2. Failing to Check and Adjust Pressures

All tires will lose air over time, and pressures will change with ambient temperature and elevation. You need to adjust pressures to set your tires up to perform on different surfaces. If you are not airing down when you leave pavement, you are setting yourself up for failure.

3. Only Buying Four Tires

Failing to run a matching spare tire within its safe lifespan is setting yourself up for disaster. In a best case scenario, this will force you to immediately seek out a tire shop in the event of a puncture. In a worst case, it will leave you stranded.

4. Not Planning Ahead

What’s going to be crowded the day before the first big snowstorm hits? Your local tire shop. Set yourself up to perform seasonal tire swaps yourself by having them mounted to a dedicated set of wheels, or pick a date on the calendar and book yourself a time slot well in advance of any rush. The same goes for replacing worn out tires. The best time to select, shop for, and mount a set of replacement tires is before the old ones wear out, not after they’ve left you stranded in the middle of nowhere.

5. Believing Groupthink

A colleague texted me the other day asking if some piece of conventional wisdom—that E-rated LTs are the best option off-road—was actually true. I was flabbergasted. Check your sources, and take advantage of good information.

6. Not Running Winter Tires

I’m never going to stop trying to hammer this point home. If you plan to drive in winter conditions, you must run a real winter tire. There is no substitute, either for your own safety, or for that of the rest of us with whom you share the road.

Wes Siler, our longtime outdoor lifestyle columnist, is a trained racing driver who has organized long-distance off-road trips across six continents. You can ask him for help selecting the right tires for your unique needs, or with any other outdoor topic, by subscribing to his Substack newsletter.